After viewing a dozen or so films at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, I noticed a common thread within all of these distinct, varied stories from authors from around the world. And it got me thinking about “pure cinema,” if such a thing exists.

I’m going to focus on two trends that are rather different, but nonetheless nearly unavoidable in movies today. One is a plot device and one deals with technique. There’s an ever-growing trend of a specific plot device which depends on violence to garner interest and attention in the viewer. The latter is overcranking the camera to 48FPS or 60FPS (in layman’s terms: the frame-rate to produce slow motion) to heighten “drama.”

It’s disappointing, given these vital parts of cinema were once revolutionary and rebellious. Using slow motion was reserved sparingly for hard impact, specifically to illustrate action in films like Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954) or Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973).

Of the 12 films I screened, 11 of them used slow-motion for dramatic effect and 7 had implied violence and featured a weapon. Now I’m not a cranky, old purist who looks down on these tools of the craft. Violence is a whole lot of fun (especially when done right like in this year’s effort by Jeremy Saulnier: Green Room) and slow-motion can be a masterful brushstroke to the screen.

Rather, I feel merely bored by the choice. It has now become an expected turn of the craft, like seeing an explosion in a Michael Bay film. I know it’s coming. That being said, when a picture rolls around sans violence or slow-mo, I’m taken aback. Almost like the first purveyors of cinema must have been taken aback by the explosive use of violence or the slowing of time during those formative years of cinema.

In Andre Bazin’s post-humous collection of writings, What is Cinema? He speaks of the use of violence:

“The screen uses violence in such a customary fashion that it seems somehow like a devalued currency, which is at one and the same time provoking and conventional.”

The modern film industry, in part, is bankrupt of originality. This is not an opinion. It’s merely the way of things. It has used violence to no end to get butts in the seats and - surprise, surprise - it’s still working. Avengers, Jurassic World, and Furious 7 have all topped $1 Billion this year and, yep, all feature a wide arsenal of weaponry.

When Fritz Lang released M in 1931, he received a backlash against the violent nature of the main character. This was within the first 30 years of the conception of cinema and the startling graphic use of violence was still fresh. By 1972, Lang was in major opposition of the way violence was being treated:

I hate violence. I am against violence - I always try to depict scenes which have nothing to do with that kind of violence that you see in Westerns… As an example, in my film M there is no violence, all this happens behind the scenes, so to speak…The violence exists in your imagination.

Even as early as 1967, Lang would go on to say:

I detest violence when it is shown as a spectacle or when it is used to make us laugh. And that is how it is used more and more on the screen. There is the same problem with love as it is incessantly shown in films.

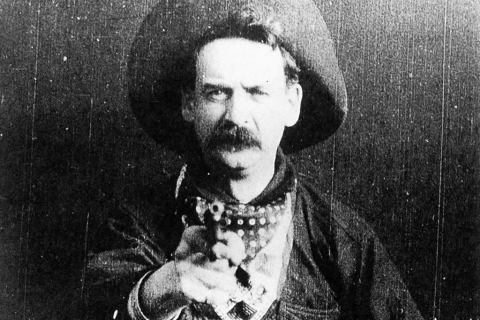

And yet, more than a century has passed since the birth of cinema and we’re still tied to the most primitive, archaic forms of entertainment. The Great Train Robbery (1903)by Edwin S. Porter depicted a man shooting his gun at the audience (it would later be homaged in 1990 by Martin Scorsese in Goodfellas) and over a hundred years later…we’re still at it.

Does this stem from a lack of imagination in cinema? Do filmmakers need to meet a quota for the industry’s demands? Or does violence still play such a major role in society that we’re always returning to its door? It’s, no doubt, a thrill to go see a shoot ‘em up like George Miller’s Mad Max (2015). But at what point does the audience become numb to it? And at what point do we find the next cutting edge of storytelling - one that’s evolved past the mere carnality of physical pain.

Not every film can be absent of violence, surely. And yet, we can’t reserve it for those who handle it the best - the Finchers, the Audiards, and the Hanekes.

Time Stands Still

Slowing down time is part of the intriguing elasticity of film time. We are not confined by seconds, but by milliseconds, frames. In The French Cinema Book, Monica Dall’Asta explains the redefinition of “pure cinema” as “plastic cinema”:

“…The notion of ‘pure cinema’ was usually employed to refer to the use of specifically cinematic means in the recording and treatment of the images. These techniques ranged from montage to superimposition, and from slow motion to the deformations produced by…filters and lens.

This appreciation of the purely plastic value of the image had a number of different implications that varied from author to author….The plastic nature of the film image was not necessarily at odds with the construction of a plot, but it could be used to integrate the narrative with ‘sensations’…memories, dreams or fantasies”

Perhaps the use of slow-motion is the author’s attempt at getting closer to the core of their character, their story. To fragment time is to perhaps give the audience a more truthful account of that perspective. Or maybe it’s cheating? Is a film by Jean Cocteau, which is full of optical tricks, symphonic editing, and superimpositions any more pure than that of Robert Bresson, who offers a more distilled interpretation of reality?

Slow-motion is definitely a crutch these days. I’m guilty of it myself. It’s a surefire way to amplify the drama, even when there is no drama (see: most car commercials). And when done well, again, it can be breath-taking. I’m thinking of the first reveal of Vickie La Motta in Raging Bull (1980)or the tragic fainting of Julie Christie’s character in Don’t Look Now (1973).

My question remains about both violence and the slow-motion technique: Given the century or so of cinema, do we not have a more creative outlet for transforming perspective? Do we not have, at our hands, an evolved emulation of pain, passion and despair? Why do we feel bound by these outdated tricks to help people lock eyes with our characters and believe them?

For all of the resources at hand, filmmakers seem to be bound by the simplest of illusions: slowing down time and simulating pain. Relics of the silent cinema.

Maybe I’m being too hard on the medium. It’s still in its primordial ooze. If you were to compare the timescale of paintings, which have been around for roughly 35,000 years (if you count the oldest cave paintings in Indonesia) to that of cinema, it is barely 2 years old. Hardly old enough to know better. And yet young enough to have the world ahead of it. Within the first year, we developed sound. The second year, colour.

It’s a young child I anticipate will grow out of its fussy, violent tantrums and crawling slowness. Soon it will be running - clear-headed and learned.